I’ve been thinking about what I wanted to write for the refreshed version of my blog. Sure, there are still a few archived drafts waiting in line, but I felt the need to create something new — or rather, something new about something old.

I wanted to write about a game that holds a special place in my heart. Not only because I recently revisited it, but also out of respect for its legacy. I truly believe that Prey (2006) is one of the most underrated first-person shooters ever made. And I’m happy to shine a bit of light on it here.

Prey isn’t just an action game with a cool story and dark atmosphere — it’s also a title with huge value from a game and level design perspective. Breaking it all down would take pages, but today I’ll focus on what matters most: the design choices, the developers’ approach, and a few examples of why this game still feels so clever. Hopefully, by the end of this post, you’ll want to play it yourself (and trust me — it’s worth it 😉).

Story time

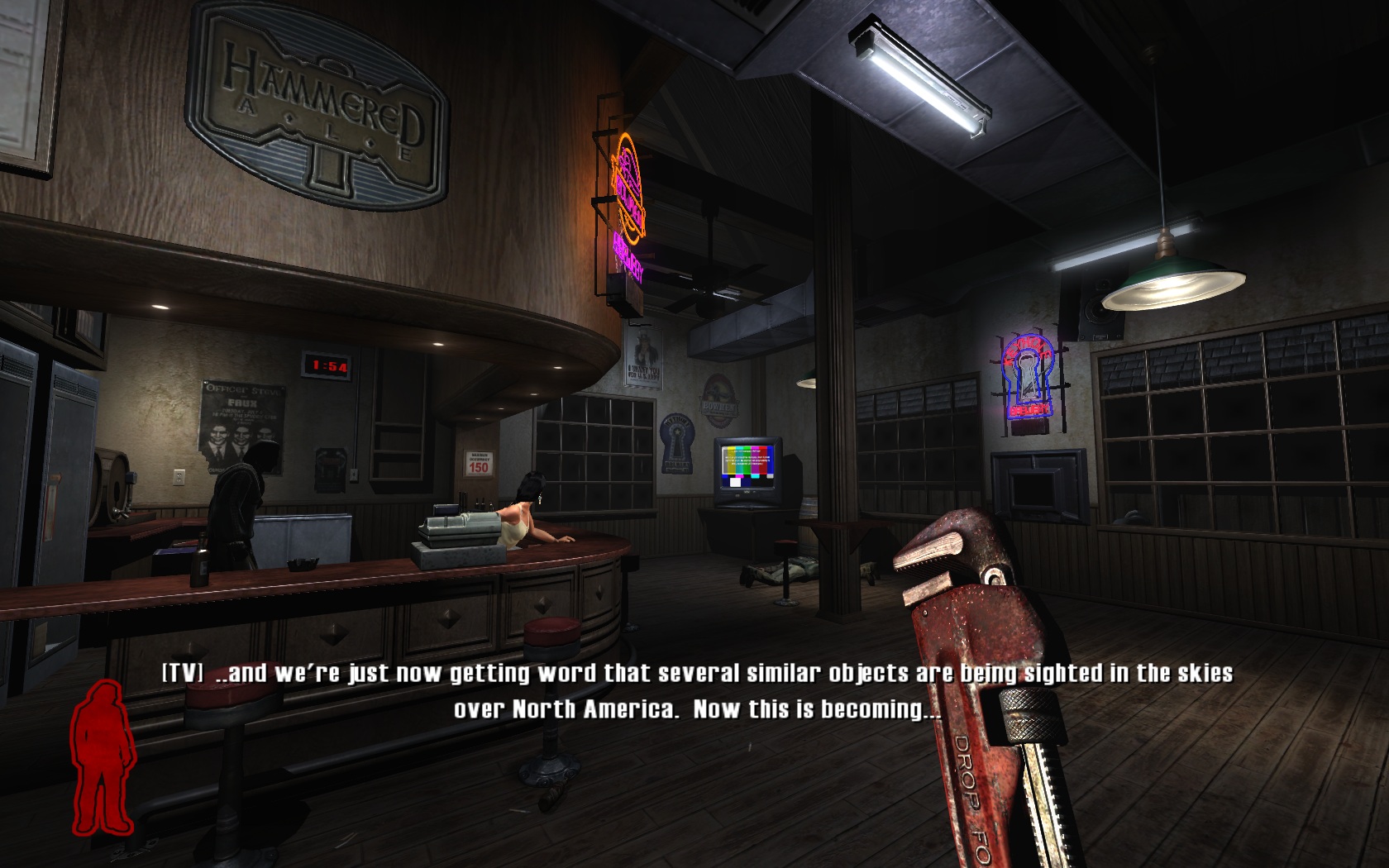

No spoilers here: you play as Tommy, a Native American living on a reservation in the US. One night, he visits his girlfriend Jen at the bar — not knowing that this will be a night unlike any other. That’s all I’ll say. The rest is better experienced firsthand.

The introduction is fantastic. Prey starts slow, at its own pace. We get to know the characters, the setting, and the tone of the whole adventure. We’re not at a military briefing — we’re simply part of the world, witnessing an event that soon spirals out of control. It feels natural, not staged. A perfect example of how environmental storytelling can draw the player in from the very first minutes.

First steps

Prey is, at its core, a first-person shooter, so of course there’s plenty of action. But the developers at Human Head Studios (RIP) knew that combat alone wouldn’t cut it. They mixed in puzzles and environmental challenges — and the best part is that you start learning them right from the beginning.

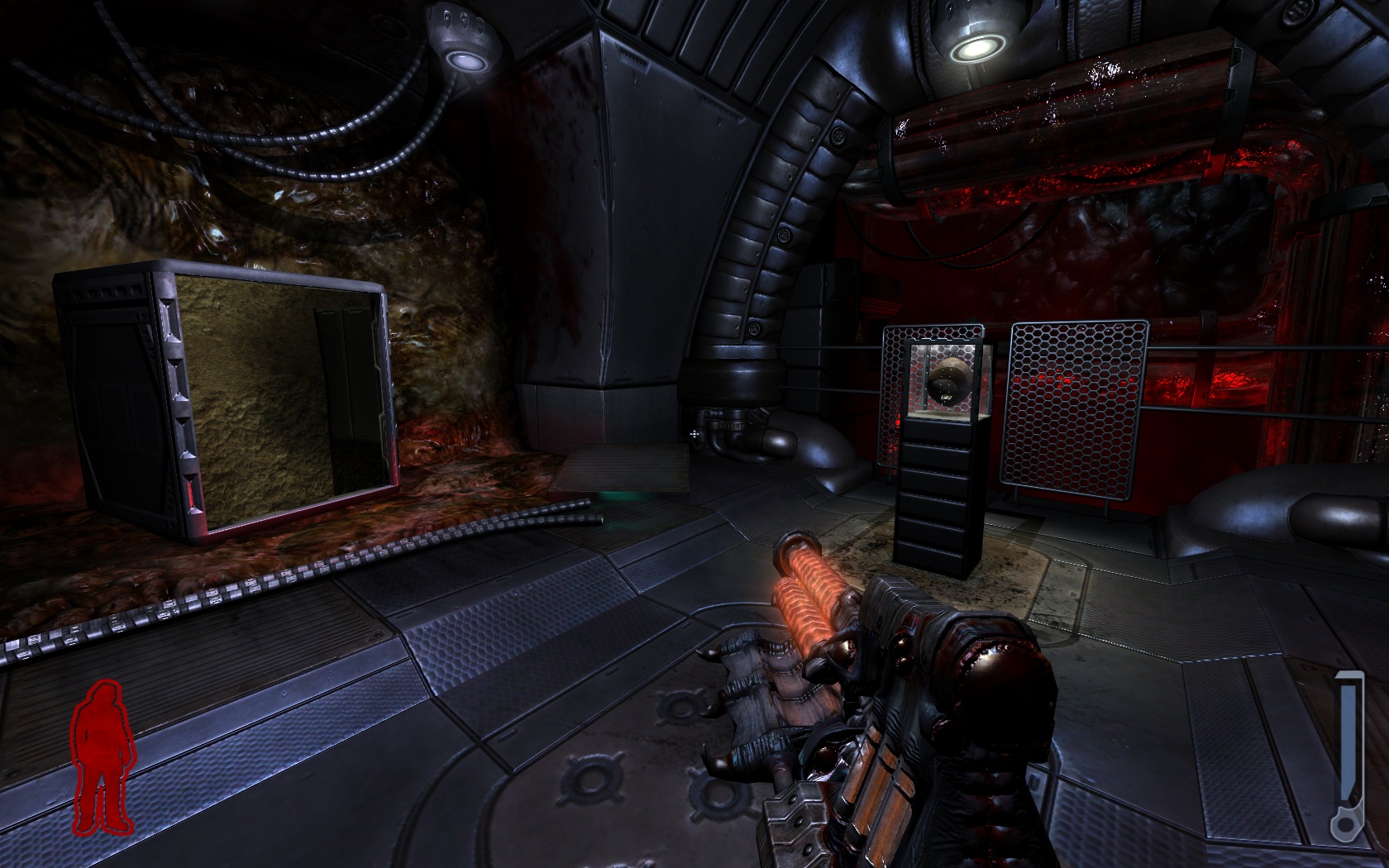

When you first pick up your trusty wrench, the game places you in a controlled environment. Early enemies are weak, letting you understand the basics without pressure. It’s a textbook example of a soft tutorial — learning by doing, not by reading. You slowly immerse yourself in the world, and as you progress, the game gradually raises the stakes and gives you new toys to play with.

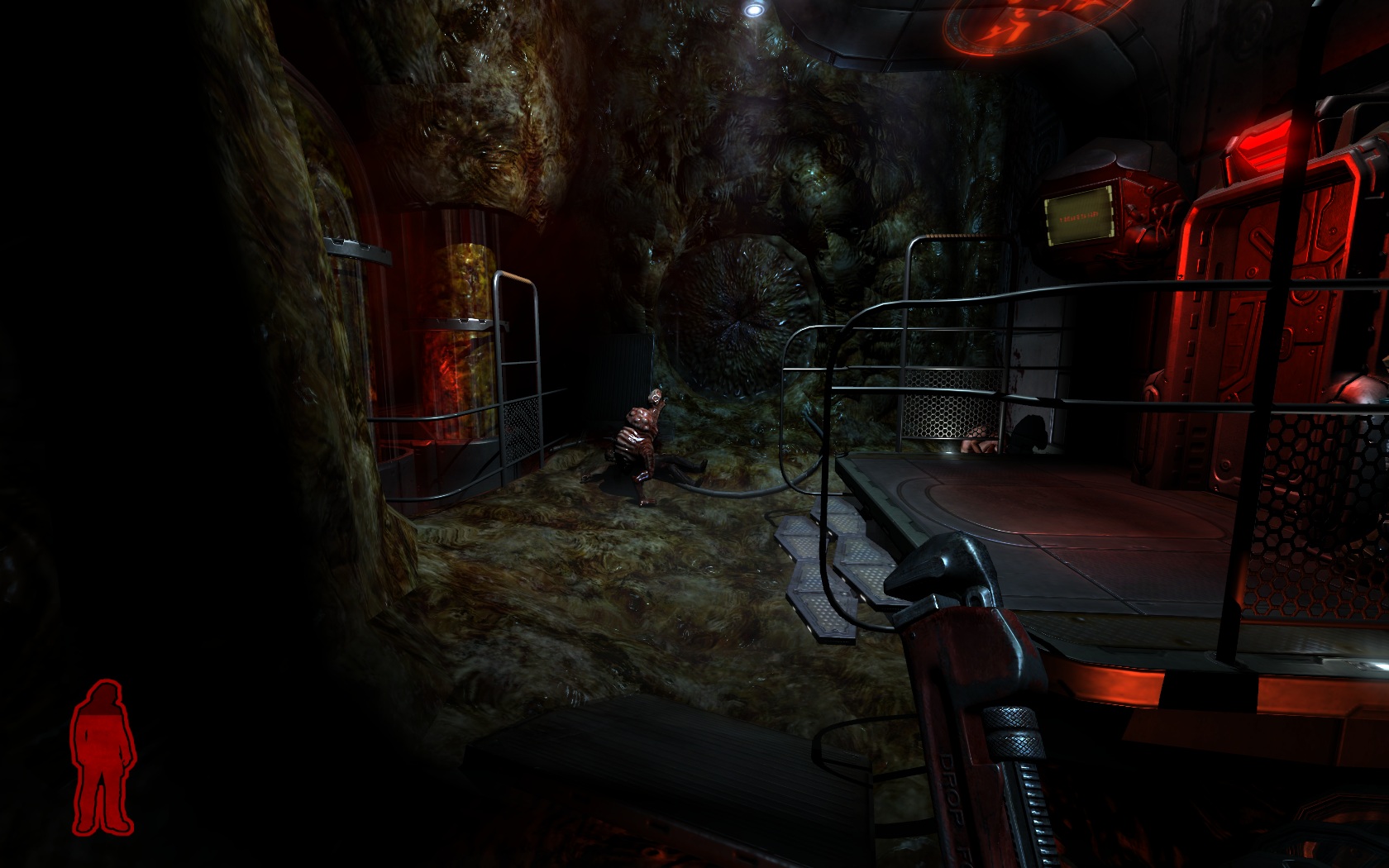

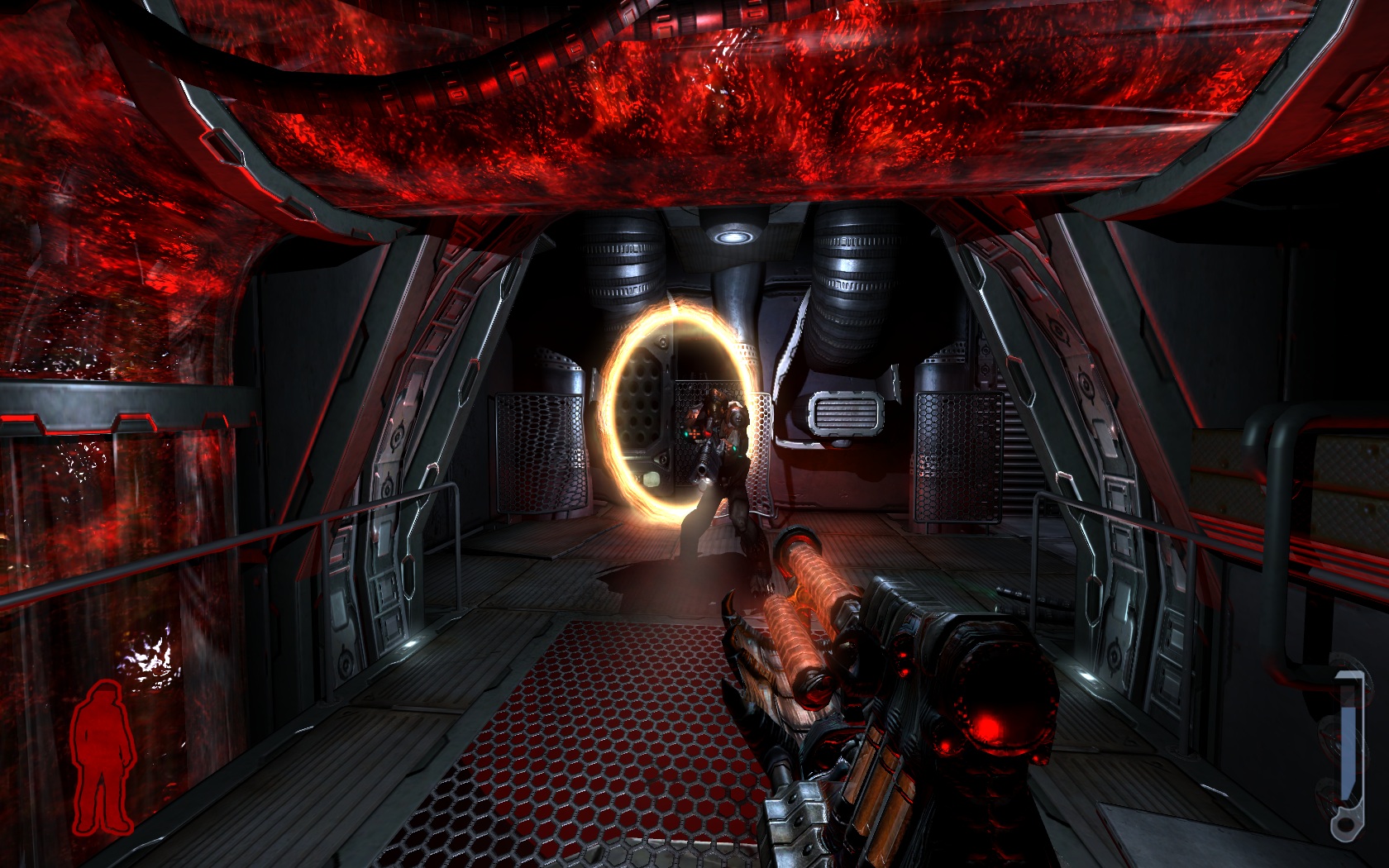

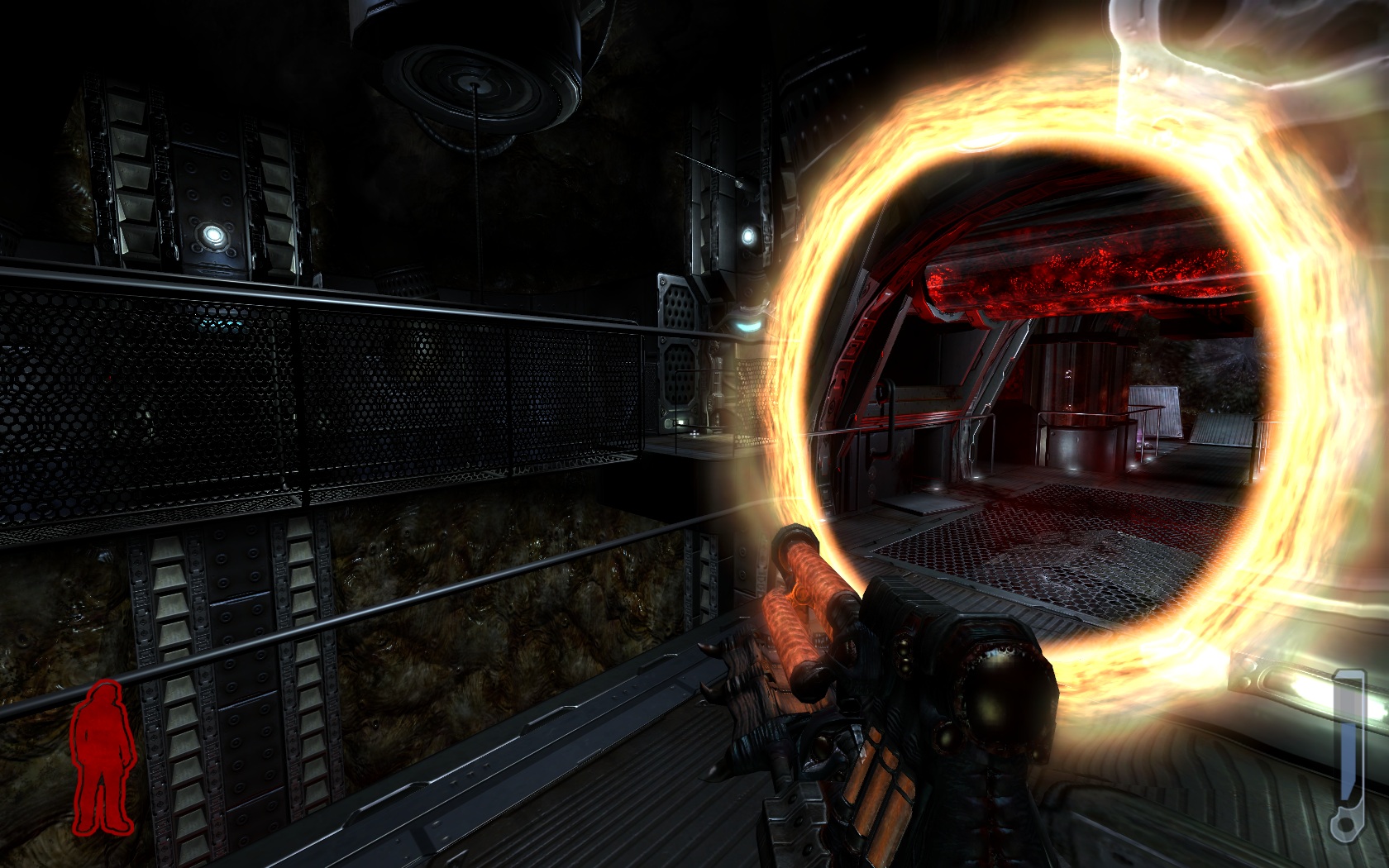

Soon you face your first enemy with a ranged weapon, appearing through a portal. That moment not only introduces a new threat, but also hints at a major mechanic — teleportation between areas. And fun fact: Prey came out a year before Portal, already experimenting with similar ideas.

Those portals are often on our linear path, leading to unexpected places (and by means pushing the story forward). This idea feels truly sci-fi and perfectly fits within the tone of the game. Not to mention that's also naturally cuts levels into small pieces for streaming/performance sake.

But that’s not the end — we’re still at the very beginning of the game, and we’ve already seen a few interesting features. One of them is rolling a huge organic “egg” that explodes near vines, destroying them and opening up a path forward. We’ve seen similar ideas before and this one is no special but it breaks the flow of combat - meaning the player is not constantly bombarded with enemies. There’s also one huge gimmick within the game (and definitely not the only one) that really stands out — the shift in geometry perspective.

A world turned upside down

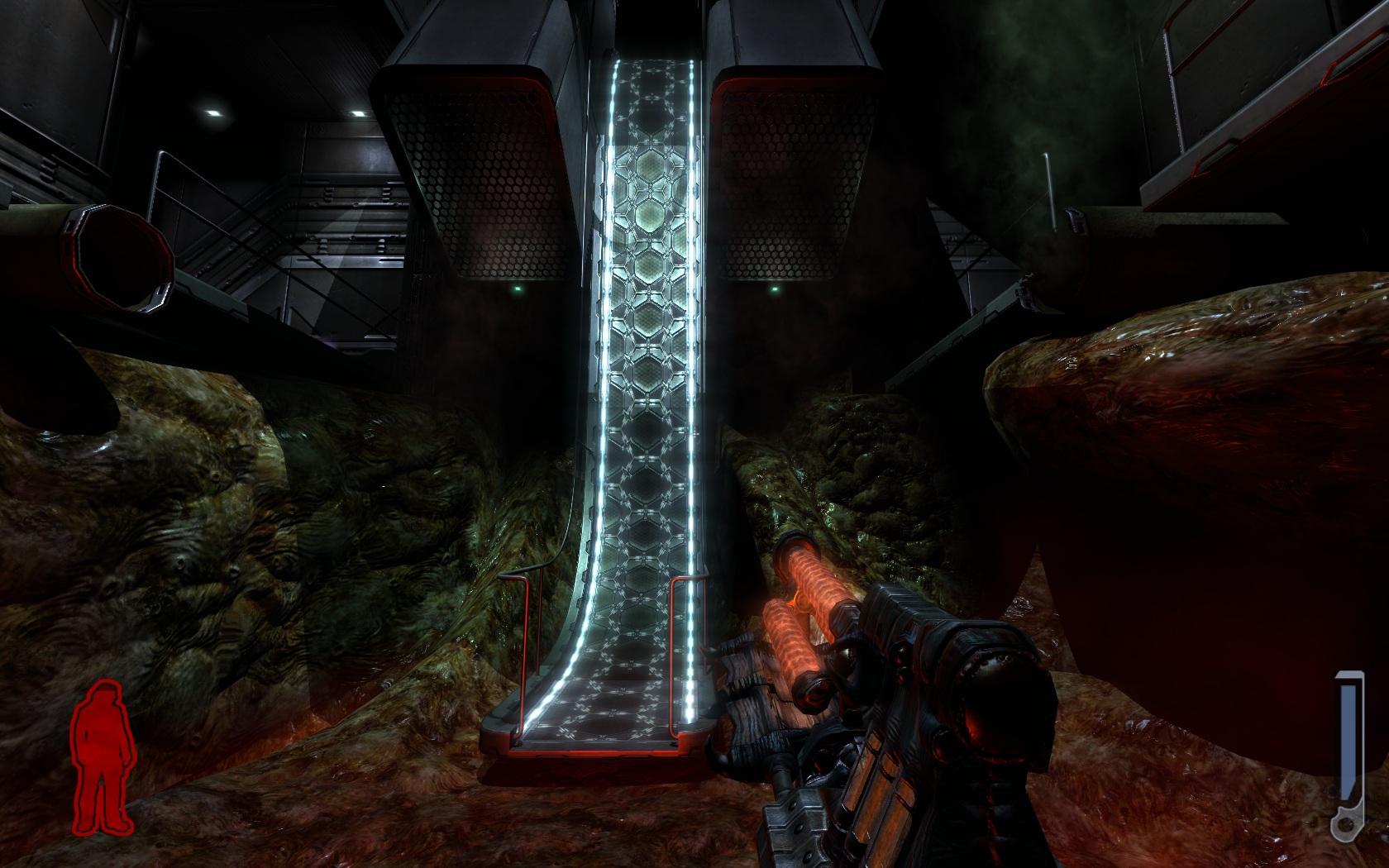

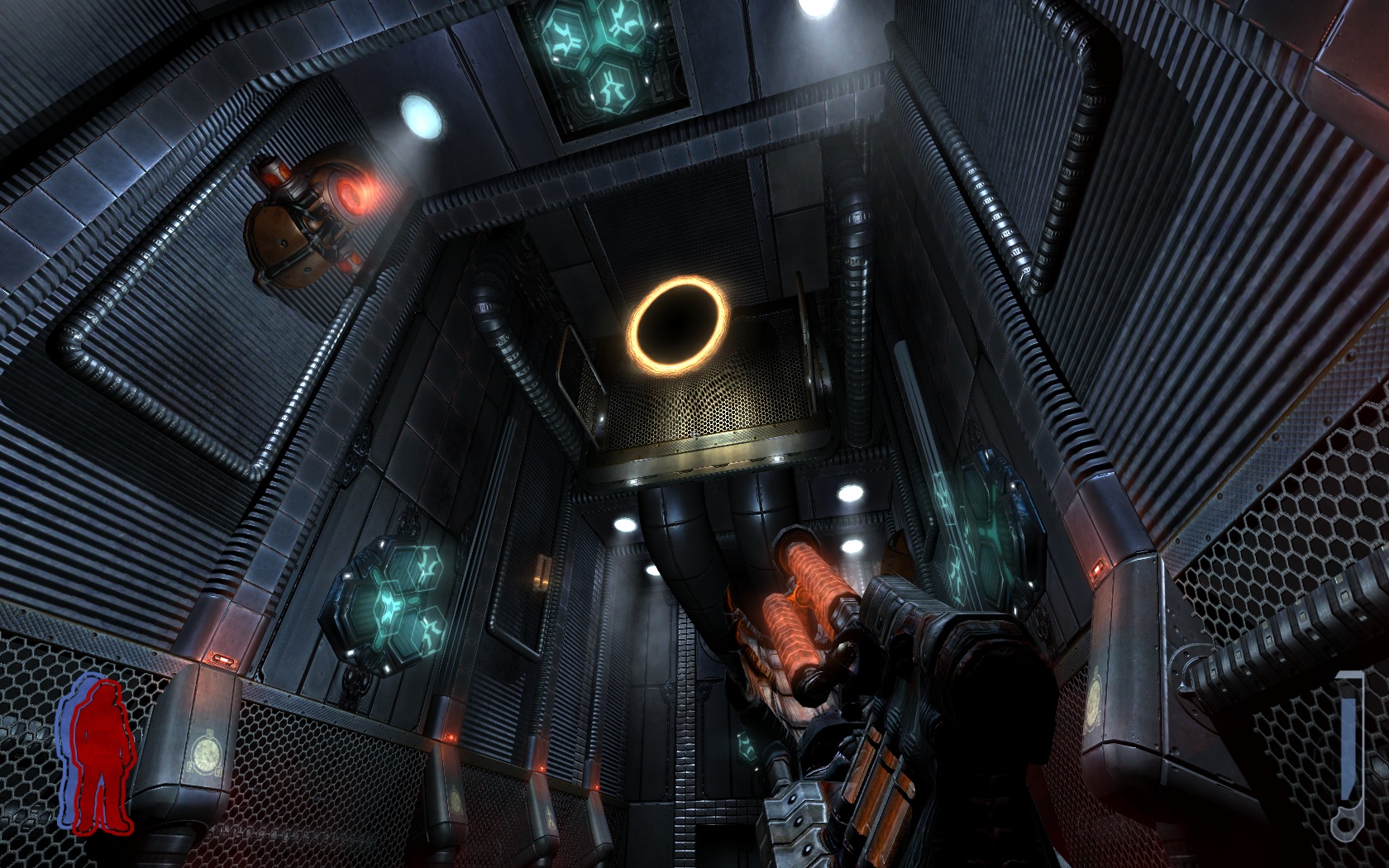

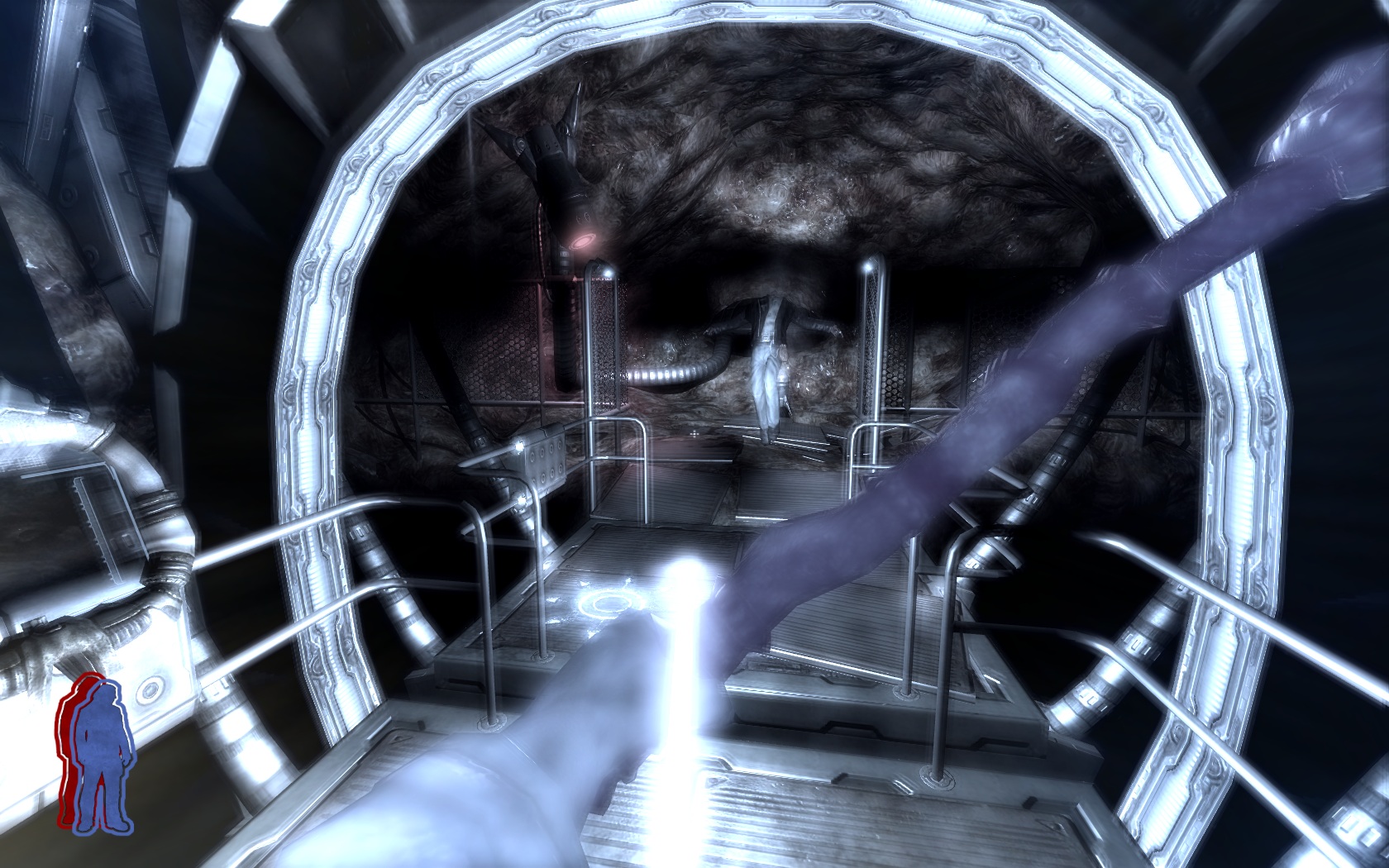

For decades, first-person games have shared one simple rule: we see the world through our character’s eyes — ground below, ceiling above, walls on the sides. But what if the ceiling became the floor? What if we could rotate the entire world by 90 degrees?

That’s exactly what Prey lets you do. You can walk along walls, flip rooms upside down, and move between orientations through special walkways or green switches that rotate the geometry. The result is a total shift in spatial awareness — you start rethinking what “up” and “down” even mean.

From a level design perspective, it’s brilliant. It not only adds variety, but also challenges the player’s perception and adaptability in 3D space. Some moments look almost comical, but that’s part of the charm — and it was a true game changer long before “mind-bending geometry” became a trend in modern game design.

Spirit walk

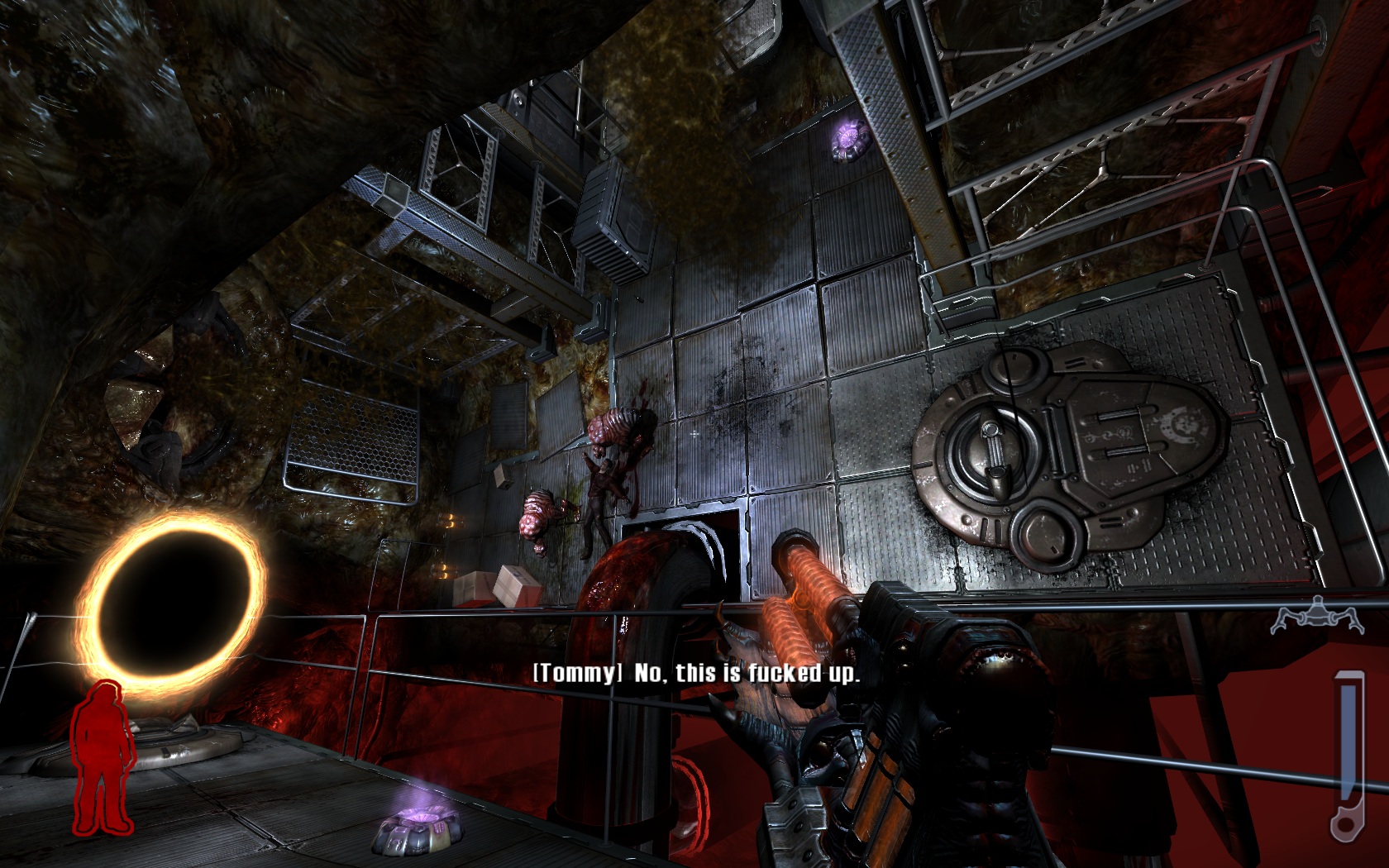

You can’t talk about Prey without mentioning its other core mechanic — the Spirit Form. Tommy can leave his body and enter the spirit world. This happens in two situations:

- When you’re fatally wounded — you shift to the spirit realm, hunt down other spirits to regain energy, and return to life.

- Or anytime you want — you can activate spirit mode manually to explore and bypass physical barriers.

This ability completely changes how you approach gameplay. On one hand, it makes the game a bit more forgiving (death isn’t the end), but on the other, it opens new ways to solve puzzles. For example: a door is locked, and the control panel is behind a force field. You can’t reach it physically… but you can pass through as a spirit. Simple. Brilliant.

The environment even gives subtle hints when to use it — like glowing sun runes painted on walls. It’s a great example of non-verbal guidance that communicates through the world itself rather than UI prompts.

Combat

And of course, the backbone of the entire game. Make no mistake, this is a First Person Shooter after all. HOWEVER. In my opinion as good as it gets, combat is only a piece of the puzzle. Yeah, sure, there are tons of enemies, some fancy weapons but combat without all the elements I've mentioned before would be only generic. Portals, spirit form, geometry changes, all these elements make combat even better.

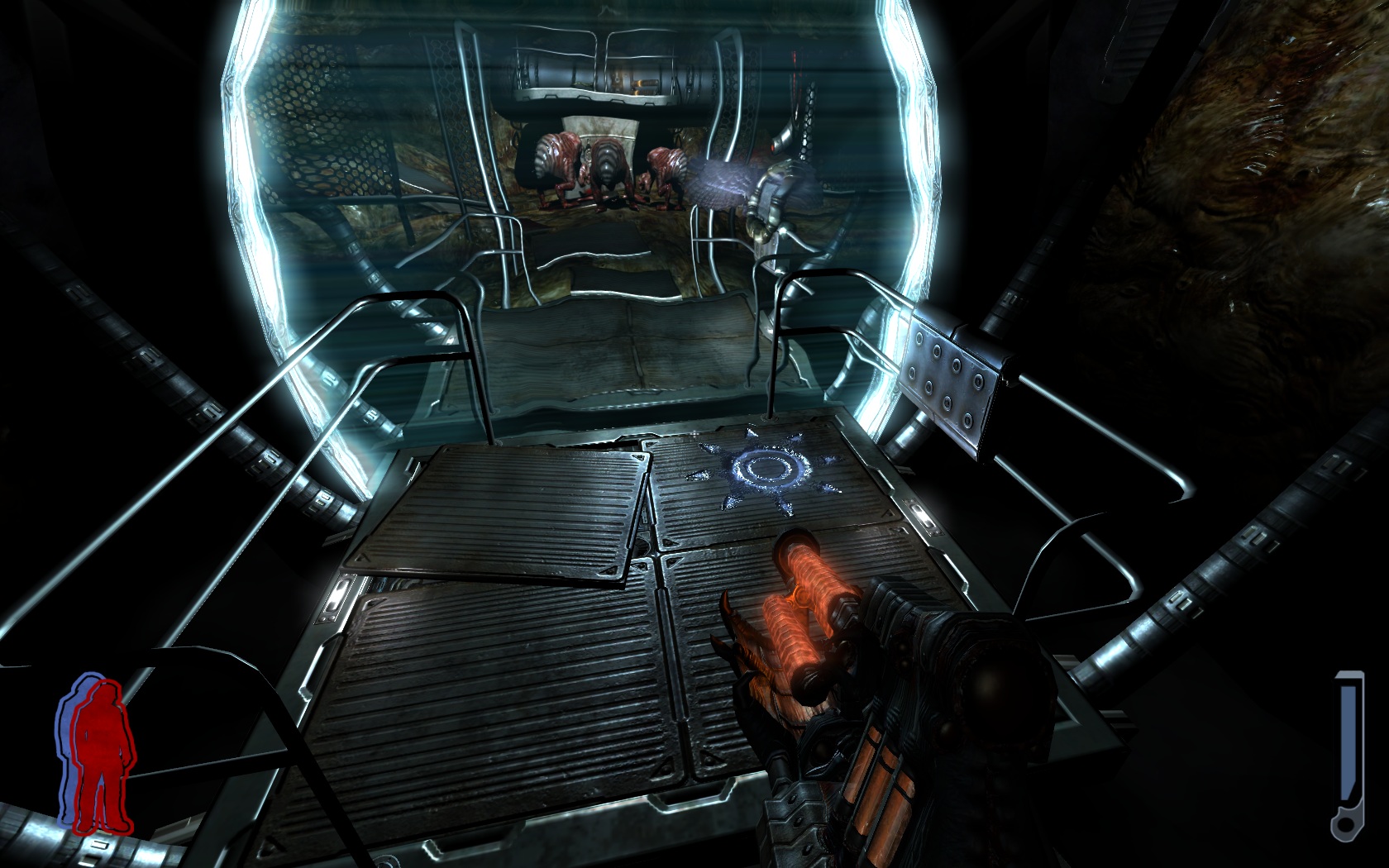

The levels are linear, with side paths usually leading to optional spots where you can grab some extra resources. The main route follows the story, giving us occasional climactic moments that ramp up the pacing. Along the way, as in most FPS games, there are combat sequences — sometimes in narrow corridors, other times in more open arenas where you have room for strategy and finesse. And, as tradition goes, before major fights the game lets you restock your ammo to make sure you’re ready for what’s ahead. 🙂

Combat spaces are often tailored to specific encounters. On larger arenas, enemies are equipped with sniper rifles, pushing you into long-range combat. Smaller areas, on the other hand, favor close-quarters fighting — it all depends on the level designer’s intention, deciding what kind of experience the player should have during that encounter.

Conclusion

Prey (2006) is a gem. Even after all these years, it’s still engaging — with its story, atmosphere, and above all, inventive design. It’s a reminder of how creative single-player games used to be, unafraid to experiment and surprise the player. If you enjoy old-school shooters with a twist, this one will grab you from the start.

Sure, the visuals have aged, but under low light the game’s eerie, organic environments still have power. It’s proof that good ideas never get old.